Introduction

Situated on the southeast coast of China with only a river between the city and the Mainland, Hong Kong is widely considered a society of immigrants, the majority of whom come from Mainland China (Law and Lee, 2006). According to the most recent Hong Kong census which took place in 2011, 93.6% of the population in the city were of Chinese descent, and 31% were born in Mainland China (C&SD, 2012).

Historically, a large number of immigrants who moved to Hong Kong from the Mainland were, in reality, refugees who sought to run away from conflicts or to seek economic opportunities (Zhang, 2005). Multiple waves of Chinese refugees turned Hong Kong from a small fishing village with less than 10,000 inhabitants into a metropolitan with over 7 million citizens (C&SD, 2012; Fan, 1974).

Many of such refugee waves, like the one during the Cultural Revolution from 1967 to 1977, have already been studied extensively, but a number of them remain less examined by researchers, including the wave prior to the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong in 1941.

At the same time, even though the population of Hong Kong has always been dominated by ethnic Chinese people, it is also a former colony of the British Empire, meaning that it was governed and ruled by British elites between 1841 and 1997, excluding when it was occupied by the Empire of Japan for 44 months from 1941 to 1945 (Snow, 2003).

This distinctive fusion of the East and the West resulted in a booming newspaper industry in which both Chinese-owned newspapers and foreign- owned newspapers (mainly by British and American businessmen) flourished with substantial amounts of readers following the press (Ding, 2014).

In this sense, it is a good idea to study how newspapers in Hong Kong, no matter if they were owned by Chinese or foreign business people, would cover a Chinese refugee wave, given that Hong Kong was essentially a British-ruled society while the refugee waves generally had a heavy Chinese-oriented background. The fact that the one prior to the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong has not been studied from the

angle of newspaper coverage before makes it a worthy topic to focus on, as this research has the potential to introduce a new area of study and provide a foundation for further research to build on.

This research is an attempt to study how Chinese-owned and foreign-owned newspapers in Hong Kong covered the refugee wave which spanned from 1937 to 1941, before the Empire of Japan occupied the city. This dissertation will start by examining the framing theory which serves as a foundation for the research.

It will then provide a succinct overview of Chinese refugee waves in Hong Kong, particularly focusing on the one before the Japanese occupation. The methodology chapter explains the rational behind the use of the quantitative content analysis method, in addition to how this particular research is developed and designed. The last chapter covers the findings and discussion, as well as a brief account of the limitations of this research.

Literature Review

Introduction

As it has been mentioned in the previous chapter, this chapter will start by looking at Goffman’s framing theory and its application in news analysis, in order to present the theoretical framework of the research. It is then followed by an explanation of the background of refugees seeking asylum in Hong Kong during the Second Sino- Japanese War and the newspaper industry in Hong Kong during the time. Previous studies done on the issue and the gap this research aims to fill are also addressed in the chapter.

The framing theory

In the field of sociology, the concept of framing was first presented by Goffman (1974, p21), who defined frames as “schemata of interpretation” that individuals use to “locate, perceive, identify and label” events and occurrences so that they are able to understand them. Gitlin (1980) applied Goffman’s theory in his study exploring how the news media reported the Student New Movement that took place in the United States in the 1960s.

By comparing news media’s reportage of the events and the personal experience of activists who engaged in them directly, Gitlin found that the media ignored the movement’s message and its effective developments and trivialised it by emphasising on aspects that would make it look deleterious, such as its militancy and conspicuousness. He defined frames as “persistent patterns of… presentation, selection, emphasis and exclusion” and concluded that they allow journalists to “process large amounts of information quickly and routinely” and “package it for efficient relay to their audiences” (Gitlin, 1980, p7). In order to work out a clear idea of how framing functions, Entman (1993) proposed that it fundamentally involves selection and salience. To frame an item, he established, is “to select aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text” to highlight certain ways to define, interpret, evaluate and treat the item (Entman, 1993, p52).

However, Scheufele believed that framing influences the audience’s opinions, not by making certain features more salient, but “by invoking interpretive schemas that influence the interpretation of incoming information” (2000, p309). Though there are different ideas about how framing operates in practice, its purpose persists to be to manipulate how information could be received and interpreted.

Gitlin’s news analysis was the first time the framing theory was ever applied on communication research, and subsequently on news research (Ardèvol-Abreu, 2015). However, even before the publication of his study, Tuchman had already identified news frames as “an essential feature of news” (1978, p193), as the author believed they were necessary in transforming meaningless episodes into palpable issues. Along the same lines, D’Angelo and Kyupers (2010, p1) noted that “journalists cannot not frame topics[,] because they need sources’ frames to make news, inevitably adding or even superimposing their own frames in the process”. In communication research, approaches to study the framing theory can generally be grouped into two: one that deals with “frame-building” and another that works on “frame-setting” (Scheufele and Tewksbury, 2007). Frame-building refers to how frames are formed and in what ways journalists adopt them in discourse – Scheufele and Tewksbury (2007) identified a number of ways journalists could be influenced to frame a certain issue, including societal norms, pressures from their organisations, interest groups and policy makers, professional routines of their occupations as well as the ideological or political beliefs of the journalists themselves. On the other hand, frame-setting is concerned with how media frames influence audiences’ opinions on issues – for instance, by showing respondents the same news stories framed in different ways, Valkenburg, Semetko and de Vreese (1999) found that how an event is framed can have significant effect on how people envisage it and what they recall of it after consuming the information.

News frames can essentially be classified into two categories: issue-specific and generic frames. Issue-specific frames can only be applied on specific topics or events and they vary based on the content and context being analysed (de Vreese, 2005). For

example, in Terkildsen and Schnell (1997), in order to study weekly print media’s coverage of the Women’s Movement from the 1950s to the 1990s in the United States, the authors used five unique frames in the research, including ‘sex roles’, ‘feminism’ and ‘anti-feminism’, which are almost impossible to be used on other topics such as war or government policies. On the other hand, generic frames are not limited by the themes of the research. They typically outline particular features of news stories and can be applied across different topics (de Vreese, 2005). Semetko and Valkenburg (2000) identified five news frames that were prevalent in press and television news (‘attribution of responsibility’, ‘conflict’, ‘human interest’, ‘economic consequences’ and ‘morality’), and found, within their research, that they were suitable for both types of stories about European integration and crime, though the frequency of certain frames being used did vary according to different topics.

Background of Mainland immigrants and refugees in Hong Kong

Hong Kong had been a part of Imperial China ever since 214 BC, and was governed as a part of Xin’an County in the Guangdong Province during the Qing dynasty before it was colonised by the United Kingdom (Bolton, 2003). As Hong Kong was originally a fishing village and salt production site, the indigenous inhabitants who were already living in the region before the colonisation were mostly farmers and fishermen (Bolton, 2003). After it was occupied by Britain, in 1841, the first population figure of Hong Kong Island showed that there were 7,450 persons residing in and around the island, including those who lived in boats and labourers who came to work on the island from Kowloon (Fan, 1974). The first mass influx of Chinese refugees into Hong Kong happened in the 1850s when the Taiping Rebellion broke out in Southern China and by 1859, the total population of Hong Kong Island had already surged to 86,941 (Fan, 1974; Ceoi, 2016). Constant conflicts and turmoil on the Mainland thereafter quickly boosted the population of Hong Kong, and most of the new residents in the city had been migrants from Mainland China who moved there (crossing the border without application and supporting documents and thus, “illegally”) due to reasons that could be grouped into two categories: to look for

survival and to seek economic opportunities (Zhang, 2005). On the one hand, conflicts without end and frequent natural disasters prompted people to scramble to socially and economically stable areas – the relentless turmoil caused by the Xinhai Revolution in 1911 forced a mass number of people from the Guangdong Province to rush into Hong Kong to take refuge over the decade that followed (Zhang, 2005), and the Great Chinese Famine between 1959 and 1961 which was partially caused by unusual weathers such as floods and droughts also provoked a huge influx of refugees from all over Mainland to flood into Hong Kong (Mizuoka, 2017). On the other hand, after Britain took control of Hong Kong, the region was established as a free port and it subsequently developed into an important trading centre. The prosperous growth of Hong Kong’s business industry and the employment and investment opportunities that came with it attracted a great number of Mainland migrants – it is said that, before the Canton-Hong Kong strike which paralysed the economy in 1925, Hong Kong was known as a place where “it [was] safe to make investment… and [was] extremely appealing to nearby markets” (Sinn, 1994, p27).

So many refugees rushed into Hong Kong after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China that the British Hong Kong Government implemented the Touch Base Policy in 1974 (in which refugees who managed to get to the urban areas could stay, whereas those did not had to be repatriated immediately) as an attempt to block them from entering the territory (Wong, Ma and Lam, 2016). However, the policy failed, and it was subsequently abolished in 1980. Up until today, any illegal Chinese immigrants detected in Hong Kong would be repatriated back to Mainland immediately according to a tougher policy on immigration control established later in 1980 (Wong, Ma and Lam, 2016). After Hong Kong was handed over to China, nowadays, a daily quota of 150 Mainland immigrants has been implemented, in which the majority are those who move to Hong Kong to reunite with their families (Ngo and Li, 2016). Additionally, the Government of Hong Kong has also carried out a number of migration schemes, such as the Quality Migrant Admission Scheme and

the Admission Scheme for Mainland Talents and Professionals, to attract high-end professionals and talents from Mainland to stay in the city (Ngo and Li, 2016).

Chinese refugees in Hong Kong between 1937 and 1941

As one of the main events leading up to World War II, Japan began the full-scale invasion of China in the Second Sino-Japanese War in July 1937, with a battle later known as the Marco Polo Bridge Incident. Beginning from the northeast part of China, the Japanese forces quickly made their way down south, capturing big cities such as Shanghai, Nanking and Wuhan along the way (Snow, 2003). In October 1938, the Japanese troops captured the city of Canton in the Guangdong Province, about 175 kilometres away from Hong Kong (Fung, 2005). Four months later, the Japanese marched further down and occupied Hainan Island, an island in the South China Sea 470 kilometres away from Hong Kong which was then a part of Guangdong (Phillips, 1980).

Even though the fall of Canton and Hainan isolated Hong Kong, as a British colony which was declared to be a neutral zone at that time, it was still safe from being attacked then (Snow, 2003). As a result, as the Japanese built up more power, more and more refugees from the Mainland rushed into Hong Kong to seek asylum. There were only about 800,000 inhabitants in Hong Kong before 1937, but the estimated number of the total population in 1941 doubled the figure, skyrocketing to 1,640,000 (Sinn, 1997; Fan, 1974). According to rough calculations by the Ministry of Transport, within a year after the war broke out in China, the population of Hong Kong increased by almost 250,000 persons (Qi, Zheng and Yan, 2015). Even more refugees fled to Hong Kong after the Japanese controlled Canton and its surrounding Pearl River Delta in mid-October 1938, with 90,000 more people entering the region than leaving in the last two months of the year (Deng and Lu, 1996). Of all of those residing in Hong Kong before the Japanese occupation at the end of 1941, more than 600,000, about 37% of the population, were refugees seeking haven in the city after the war erupted in Mainland China (Ting, 1997).

All kinds of people from different sectors and levels of the society became refugees during the war – there were wealthy merchants and capitalists who continued to live a luxurious life after fleeing to Hong Kong, as well as scholars and culturati who established newspapers and produced literature to actively develop cultural undertakings (Tsai, 2001; Zhang, 1994). However, most of them were ordinary civilians scrambling for their lives. Life was tough for them, as it was extremely difficult to even find a place to live. Those who were unable to find a shelter had no choice but to live on the streets – in the summer of 1938, there were 13,000 and 17,000 homeless people respectively on Hong Kong Island and in Kowloon (Zhang, 1994). Those who did find a place were in arduous circumstances, as well. According to a survey done in July 1941, in one case, there were 497 refugees living in just 14 flats (Endacott, 1978, p12). As the population was too densely concentrated, the sanitary conditions quickly worsened and led to the outbreak of smallpox and cholera. The difficult living conditions of the refugees never got solved before the fall of Hong Kong (Zhang, 1994).

Hong Kong was originally a region where Chinese people could enter and leave without restrictions, which was one of the reasons why mass influx of refugees entered the region over time. As the battles in Guangdong intensified in 1938, fearing that there would not be enough food supplies and the condition of public hygiene would worsen if refugees continued to enter Hong Kong without constraint, Sir Northcote, the Governor of Hong Kong at the time, issued an emergency decree to limit refugees from entering by sea by asking for an entrance fee of 20 Hong Kong Dollars per person (which was later risen to 100 HKD) (Zhang, 1994).

The Government of British Hong Kong, on the one hand, limited the number of refugees from entering the region, on the other hand, built several refugee camps to succour those who were already in Hong Kong. By March 1939, more than ten

refugee camps which took in 12,299 persons had been built all over the main districts of Hong Kong (Zhang, 1994).

Plenty of individuals and different organisations also took part in aiding those who needed support. According to Mak Sik-bong, who was a primary school student in Kowloon during the refugee wave, many schools initiated refugee relief movements and appealed to citizens to donate money and old clothes to refugees (Lau and Zhou, 2009). Feng Kei-coeng, who lived in New Territories during the time, also recalled that local communities and trade unions would get together to give away food and duvets to refugees to help them survive. He added that these support groups would also help remove bodies when some of the refugees died (Lau and Zhou, 2009). In addition, a great number of charities, such as the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals and the Salvation Army, and aid societies which were founded specifically to help refugees caused by the war, such as the Chinese Women’s Club and the Wartime Child Welfare Association, also did their best in relieving refugees who were in need of support (Qin, 2003). In 1938, the Hong Kong Government reported that “one of the most prominent features of this year’s refugee problem is the immediate response from all parts of the society to the call for succouring the refugees” (Zhang, 1994, p138-189).

As the Chinese refugees in Hong Kong came from all levels of social classes, the impact the refugee wave brought to Hong Kong was multifaceted. The influx of refugees resulted in the shortage of goods and materials and frenzied inflation of prices. People who could not afford meat and vegetables could only depend on limited amounts of coarse cereals to survive, which led to many cases of people dying of malnutrition (Qin, 2003). The refugee wave also led to a surfeit of cheap labour, making the already gloomy job market even harsher. The number of unemployed people hiked dramatically, and hunger, poverty and diseases drove people to commit crimes and suicide (Qin, 2003; Yu, 2009). However, on the other hand, the cheap labour force also improved the productivity of the manufacturing industry, stimulating

the development of Hong Kong’s economy (Zhang,1994). In addition, the industrialists and businessmen who fled to Hong Kong brought in capital and technology, establishing a solid foundation for the city’s economic recovery after the war (Yan, 2008). The culturati and activists who moved to Hong Kong during the same period of time founded more than a hundred newspapers and magazines to advocate fighting against aggression and saving the nation, which significantly helped in awakening the patriotic spirit among the general public (Zhang, 1994).

The newspaper industry in Hong Kong during the time

According to Kobayashi and Shibata (2016), 39 newspapers were published in Hong Kong between the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the fall of Hong Kong, including 31 in Chinese and eight in English. Some of them were already founded before the period, such as the Universal Circulating Herald, which was founded in 1874; some were founded within the time period, such as the Sing Tao Daily, which began its publication in 1938 and is still publishing today. There were also a number of papers that were first published in Mainland, but then had to move to Hong Kong due to the war, such as Shun Pao, which was first published in Shanghai and moved the issuance to Hong Kong in December 1937 after having been forced to halt their publication for four months (Chan, 2018).

The Department of Chinese Affairs founded the Office of News Inspection to supervise the content published in newspapers in 1928 (Joeng, 2013). All newspapers had to send their articles to the office to be examined, and the materials could only be published if the inspectors approved them (Chen, 1987, p217). After the war broke out in the Mainland, according to the Department, since Hong Kong was a neutral zone, Chinese newspapers in Hong Kong should not prejudice in favour of either side nor should they use “insulting” words to address nations the British Empire was friendly with, such as “enemy” or “massacre” (Sa, 1946). The policy was met with waves of dissatisfaction. As a way to express their disapproval, journalists would use “x”, squares or circles in place of the prohibited words. In more extreme cases, the

entire position originally planned for the article would be left blank except for “full text inspected” written on it – however, this practice would also be banned later as the war approached closer to Hong Kong (Chan, 2018). It is important to note that the inspection was a lot stricter on Chinese-language newspapers than on English- language ones, to the extent that some news pieces that were permitted to be published on English newspapers were not allowed on Chinese newspapers, which further reduced Chinese newspapers’ status (Chan, 2018).

Previous research and gap in study

Even though not many, some research and studies have been done on the refugee wave in question. Zhang (1994) gave an overview of the general situation of the refugees’ lives in Hong Kong, the measures the government undertook to deal with the situation and the influences the refugees brought to Hong Kong; Yan (2008) focused specifically on the economic aspect of the refugees’ impact on the society; Deng (2018) introduced a number of relief organisations that helped in aiding the refugees; Vrzic (2013), as a postgraduate dissertation, examined the policies the Hong Kong Government used to handle the mass influx of refugees. A number of newspaper materials were used in Vrzic (2013) to explore the reality of refugees’ lives during the period, however, these newspapers were only used as supporting materials and were not critically studied. Similarly, in Ding (2014), which examined the interlacing relationship of the Overseas Chinese Daily News and the development of the Chinese society in Hong Kong, briefly mentioned that the newspaper devotedly advocated helping Mainland refugees during multiple refugee waves over the past century. There have not been any studies that focus on the newspaper coverage of the refugee wave between 1937 and 1941. As a result, this research seeks to fill in the gap in the area of study and hopes to provide a basic foundation for further studies on the topic.

Methodology

Introduction

This study aims to examine how newspapers in Hong Kong framed the refugee wave from Mainland China to Hong Kong during the Second Sino-Japanese War which took place between July 1937 and December 1941. While the previous chapter looked at the theory and background this research was built on, this chapter introduces the data collecting method as well as the design, the selected sample and the coding of the research.

Research questions

This research focuses on the media’s approach to frame the refugee wave in question, instead of examining the possible effects the news articles selected could have had on their readers. By applying the framing theory to analyse the news articles selected, this study aims to answer the main research question: how were refugees from Mainland China portrayed by newspapers in Hong Kong between 1937 and 1941? In order to better answer the question, three sub-questions were also proposed:

RQ1: What types of stories were most reported about the refugees?

RQ2: What were the papers’ stances on the refugees, judging from the way they covered the situation?

RQ3: What were the differences, if there were any, between the way Chinese-owned newspapers and foreign-owned newspapers reported the situation?

Content analysis

Quantitative content analysis was selected to be the best method to answer the research questions. This method is defined as a technique for “making inferences by systematically and objectively identifying special characteristics of messages” (Holsti, 1968, p608). According to Hesse-Biber and Leavy, content analysis is appropriate for studying “mass-mediated representation of historical events” (2011, p228) and a great

number of studies have used this method to examine such occurrences. In addition, Lutz and Collins noted that, as content analysis is suitable for conducting research that works with a large amount of data, it allows researchers to “identify and compare the patterns of representation that are regularly unnoticed and elusive to detect” (1993, p89). Furthermore, Berelson suggested five main purposes of conducting a content analysis, including “to describe substance and form characteristics of message content” and “to make inferences to producers of content” (1952, p18). The aims of the research method worked well with the research at hand, as the three sub-questions all tried to find out either the characteristics of the news articles or what opinions the newspapers produced.

Moreover, though content analysis, in its earlier stage, was classified to be only a quantitative method, as it became more employed by studies, it now can work as either a quantitative or a qualitative method (Lasswell, 1948; Berelson, 1952; Shoemaker and Reese, 1996). However, as Macnamara (2005) summarised, while quantitative content analysis can produce reliable findings by conducting statistical research, qualitative content analysis is less scientifically reliable, as it relies heavily on the researcher’s subjective interpretation on the text’s likely meaning to audiences. Therefore, all aspects considered, it can be concluded that quantitative content analysis was a suitable method to use for this research.

The most prominent feature of conducting content analysis is that the researchers must construct content categories to classify the texts being studied. Content analysis is fundamentally a “coding operation”, which is the process of “transforming raw data into a [standardised] form” (Babbie, 2013, p300) by placing units of analysis into content categories (Wimmer and Dominick, 2011). According to Wimmer and Dominick, for content categories to work, they must be “mutually exclusive, exhaustive and reliable” (2011, p169), meaning that one unit can only be placed in one category, that there must be a category for every unit to be placed into, and that different coders should, most of the time, agree with the placement of the units. An

intercoder reliability test would usually be utilised during the research, in which independent coders would code the units into categories by using the same coding scheme as the main researcher, to make sure the coding of units is consistent and reliable (Neuendorf, 2002).

Content analysis is an adaptable research method, as it can be used to study a wide range of texts and materials (Rose, Spinks and Canhoto, 2014). It is also an unobtrusive research method, because the findings would be less likely to be disrupted by subject reactivity (Webb et al., 1968). However, bias could potentially emerge during the process of sampling and coding, as the coding process inevitably requires the researcher’s own interpretation of materials, even if the content seemed clear and straightforward (Insch, Moore and Murphy, 1997). Furthermore, when conducting content analysis, there is a certain level of risk for researchers to overlook what is hidden or is not being said in the texts, which could lead to inaccurate judgments (Rose, Spinks and Canhoto, 2014).

Sampling

The Old Hong Kong Newspapers Collection, a database which provides digitised images of a selection of old Hong Kong newspapers, was used to retrieve newspaper articles needed for the research. The research studied articles that talked about or were related to Chinese refugees in Hong Kong between October 13, 1938 and December 13, 1938. As it was mentioned in the literature review, after the Japanese Army attacked the city of Canton, a large number of refugees rushed into Hong Kong (Deng and Lu, 1996). The start date was designated as the attack began in October 12, 1938 and newspapers usually report on events that happen on the previous day (Ta Kung Pao, 1938), and the specific two-month period was selected so as to focus on a limited time frame representative of the entire refugee wave. After a close examination of all editions of Ta Kung Pao and The China Mail in the database that were within the time frame, a total of 155 articles were identified, and each article was used as a primary

unit of analysis. Out of the entire sample, 114 articles were identified from Ta Kung Pao, and 41 from The China Mail.

Ta Kung Pao (大公報) is a Chinese-language newspaper which was first founded in 1902 in the city of Tianjin (Chan, 2018). In 1926, it was bought by a company set up by Wu Dingchang, Zhang Jiluan and Hu Zhengzhi, a famous entrepreneur and two influential journalists in China, and its main office was later moved to Hong Kong during the Second Sino-Japanese War (Zhao and Sun, 2018). A paper known to be accurate, timely and highly involved in social and political discourse, in 1941, Ta

Kung Pao was awarded the Missouri Honor Medal, a prestigious journalism award presented by the Missouri School of Journalism, for its “rich and essential domestic and international reports” and “brave and sharp social commentaries [that] had a huge impact on public opinions” during the war (Zhao and Sun, 2018, p62). On the other hand, The China Mail was founded in 1845 by a Scottish publisher named Andrew Shortrede and received the support of Jardine, Matheson & Co., a trading company originally from Scotland (Lee, 2000; Ding, 2014). It developed into one of the most influential English-language newspapers in Hong Kong and the longest-running newspaper in the city until its closure in 1974 (Lee, 2000). Since RQ3 aims to observe the differences between the reportage of Chinese-owned newspapers and foreign- owned newspapers on the refugee wave, it could be assumed that these two newspapers were suitable to act as representations of Chinese and foreign publications.

Coding

In order to answer the research questions, three groups, which could also be addressed as variables, were used to code the units. The variables, namely the tone of addressing refugees, the content and the typology of the article, were chosen guided by a deductive approach, as an inductive approach in which the researcher groups the variables after they are observed could cause “major biases and invalidity in a study”

(Macnamara, 2005, p9). The categories were constructed after the researcher conducted prior examinations on existing literature on media content analysis and a review on a sub-sample of 10% (16 articles) of this research’s entire sample collected through simple random sampling. A coding manual (see Appendix 1) was developed to ensure the systematic coding of data. The categories are defined and explained as follows.

• Tone of article (Specifically towards the refugees):

The articles’ tones when discussing the refugees were measured as hostile, neutral/factual and sympathetic. The hostile tone referred to an attitude clearly negative towards the refugees, especially if words such as dirty and awful in The

China Mail and 惡劣_ (odious)1 and 不逞 (troublesome) in Ta Kung Pao were used on the refugees. Correspondingly, the sympathetic tone referred to an attitude clearly supportive of the refugees, especially if words such as pitiful and

distressed in The China Mail and 淒慘 (wretched) and 辛酸 (miserable) in Ta Kung Pao were used. The neutral/factual tone was selected when the issue in the article was explained in an objective way or when it was presented by solely facts that elicited no hostile or sympathetic connections.

• Content of article

As it has been noted in the literature review, there are five prominent news frames (‘attribution of responsibility’, ‘conflict’, ‘human interest’, ‘economic consequences’ and ‘morality’) which could be used to discuss a wide range of topics (Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000). The theory has been used by a considerable number of researchers, such as d’Haenens and de Lange (2001) and Coman and Cmeciu (2014), to study news coverage of different issues and has been proven to be a reliable framework. The coding of this category was

1 The author is a native Chinese speaker and all translations were done by herself with the help of the Collins Chinese Dictionary.

predominately based on Semetko and Valkenburg’s idea, and after the sub-sample was reviewed, slight changes were made to the established news frames and more specific frames were identified to better reflect topics existed in the sample. In the end, nine frames were identified and were coded as follows.

- Human interest

- Responsibility

- Conflict

- Negative impact

- Positive impact

- Refugee management

- Refugee life and circumstance

- Traffic of refugees

- Morality

When more than one frame was displayed in an article, the principal one would be selected. The importance of the frames was measured by a list of yes/no framing questions developed by Semetko and Valkenburg (2000) and revised questions the researcher generated on the basis of Semetko and Valkenburg’s design which accommodated to specific frames developed for this research. The frame with the highest number of questions answered positively would be considered to be of the greatest importance and hence, the principal frame. When more than one frame were answered positively with the same amount of questions, the title of the article would be taken into account as to which topic was the most essential part of the piece. The questions are presented in the coding manual.

• Type of article

The typology of the news pieces was categorised as news article, feature, opinion and other. News articles are defined as “straightforward reporting” which does not usually contain analysis or comments by the journalist (Keeble, 2001, p95).

Features, which have been described as “factual short stories”, are usually written

with a more narrative approach than straightforward news articles and tend to be less objective, as well, as they offer particular perceptions and attitudes (Garrison, 1999, p89). Opinion pieces, such as editorials, commentaries and columns, were grouped together regardless of who the authors were, as they all fell into the category of opinion journalism. Articles that could not be fitted into any of the mentioned categories were sorted into the “other” group.

Findings and Discussion

Introduction

This chapter presents the findings of the research, discusses its outcomes and answers the research questions presented in the previous chapter. Its limitations are addressed, and suggestions for future research are offered, as well.

Research Question 1

The first research question asked what types of stories were most reported about the refugees. The question was examined from two perspectives – one was the typology of the coded articles, the other was the content of the articles related to refugees.

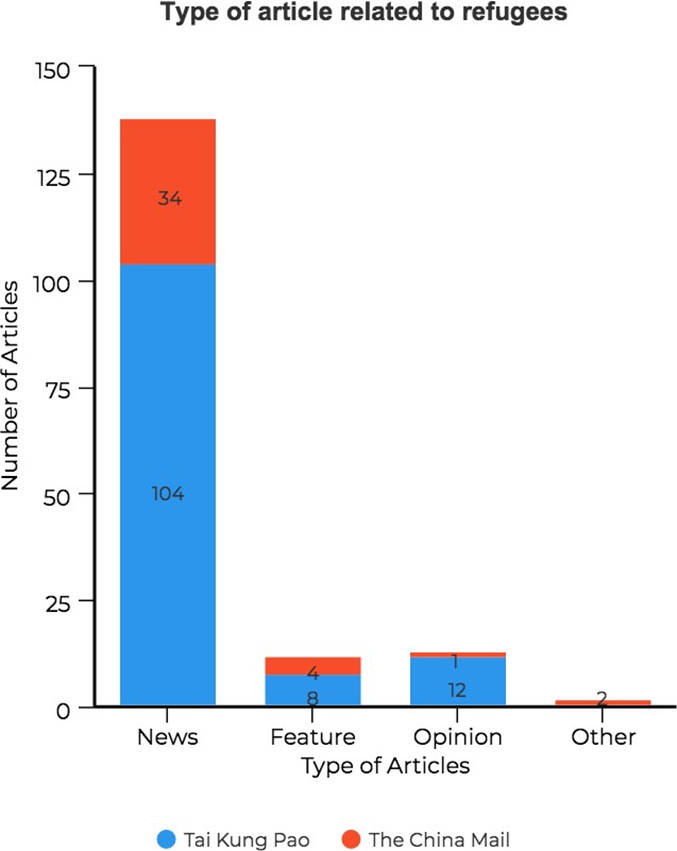

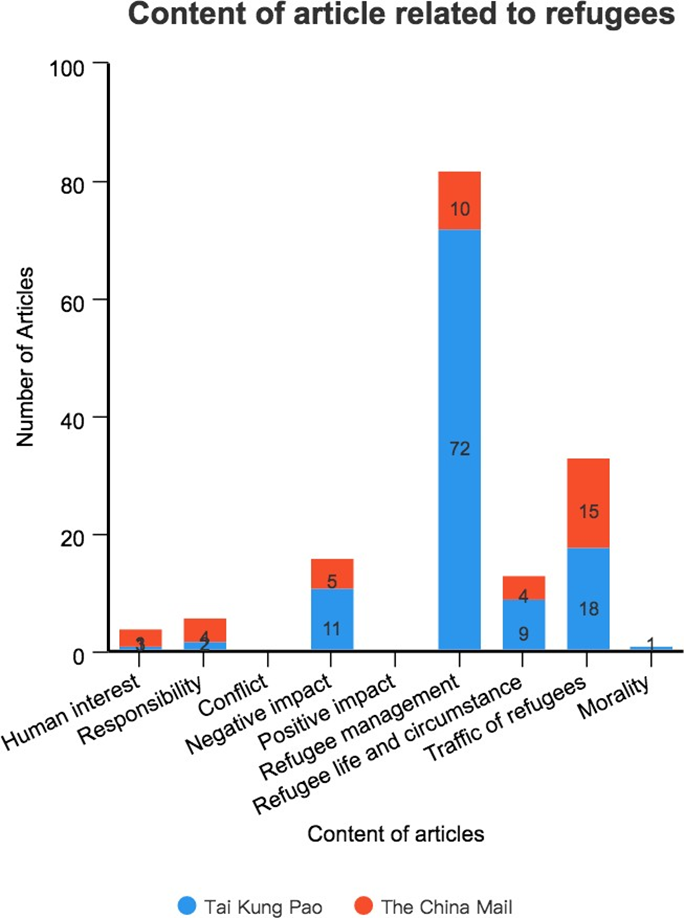

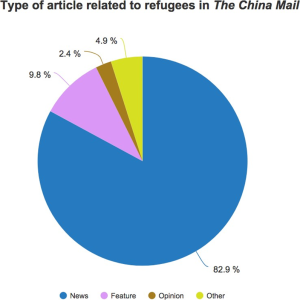

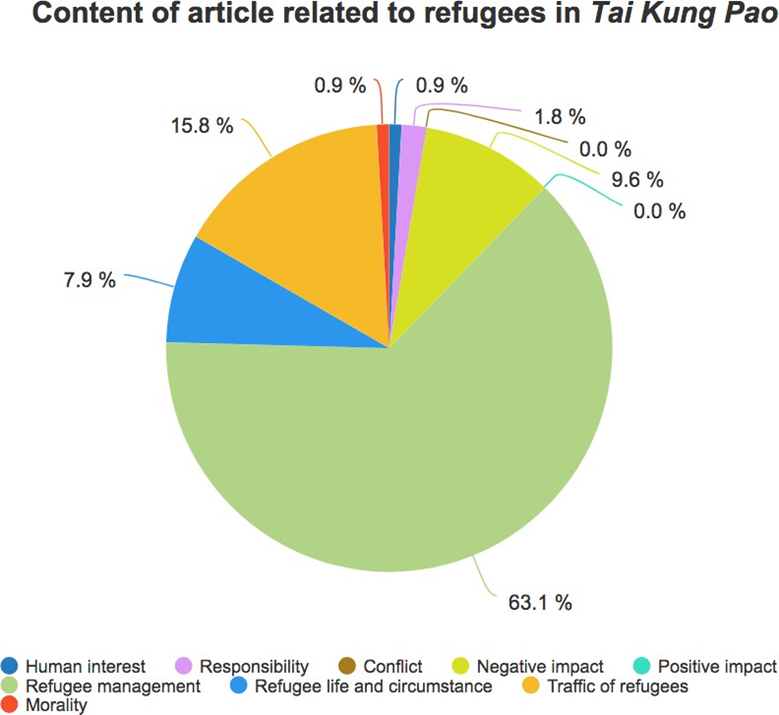

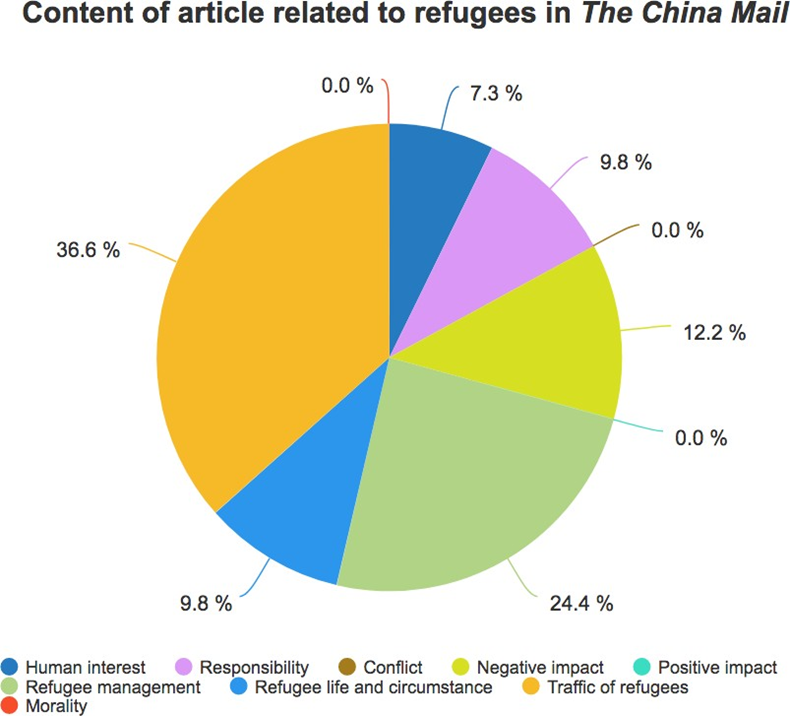

It can be interpreted from Graph 1 that the newspapers, by far, used news articles the most to report about the refugees. From Graph 2, it can be noted that the refugee management frame was employed the most by the newspapers – especially Tai Kung Pao – whereas the conflict frame and the positive impact frame were not used at all in the sample.

Graph 1

Graph 2

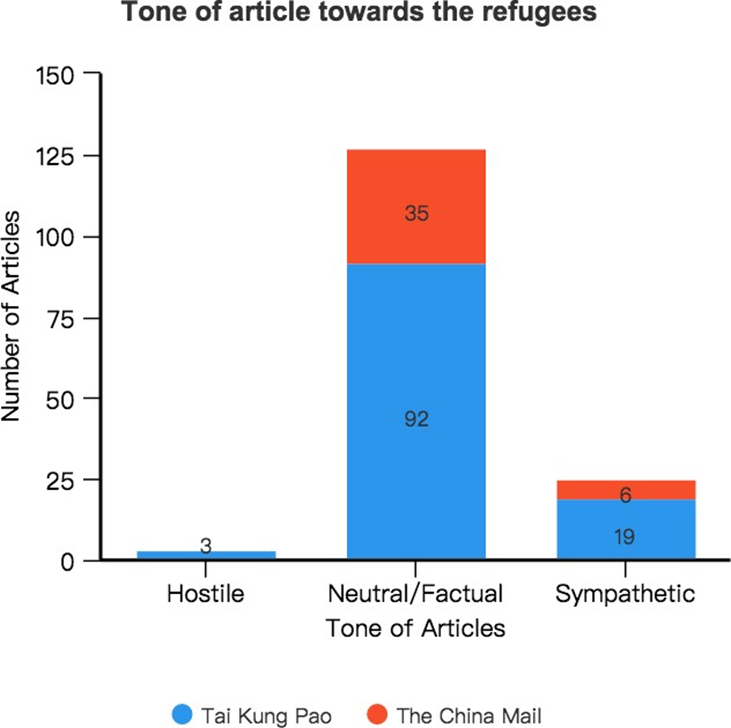

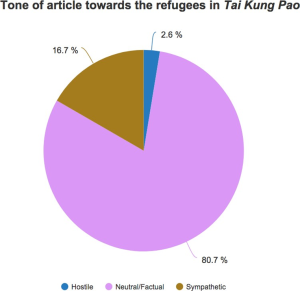

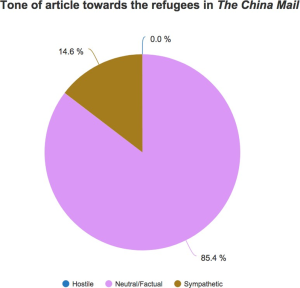

Research Question 2

The second research question aimed to identify what the papers’ stances were on the refugees. Judging from Graph 3, most of the articles in both newspapers were neutral or factual in terms of how they addressed the refugees, while a handful of articles could be interpreted as having sympathetic undertones when talking about them. For example, in a feature published in Tai Kung Pao on November 17, 1938, it was written that, “as I think back on the miserable condition faced by the old man who

was too sorrowful to cry, I cannot help but shed tears of sympathy for them”.2 Similarly, The China Mail published a news piece on November 25, 1938 in which the paper used “pitiful” and “unfortunate” to describe the scene of refugees pouring into Hong Kong. Three articles in Tai Kung Pao were hostile towards the refugees, whereas there were none in The China Mail. On the whole, it could be assumed that both Tai Kung Pao and The China Mail were mostly compassionate about the refugees seeking asylum in the city.

Graph 3

2 The original text in the feature reads “我回想着那位欲哭無淚的老者的愁苦情形、真不免要替他們撒一掬同情之淚、”

Research Question 3

The third research question wished to find out if there were any differences between how Chinese-owned newspapers and foreign-owned newspapers reported the refugee wave. The question was examined from three perspectives in which the typologies of articles, the tones used in the stories and the content written in the pieces were compared between the two newspapers.

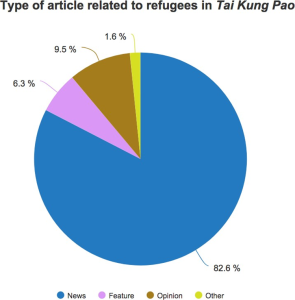

As it is shown in Graph 4 and 5, both Tai Kung Pao and The China Mail primarily used news articles to write about the refugees. Comparatively, opinion pieces, in which most of them advocated helping the refugees, were used in Tai Kung Pao more, whereas features, in which the writers talked to refugees on-site at the border or the refugee camps and got to know how they managed to cross the border or what their lives were like at the camps, were used more in The China Mail, but the proportions were both fairly small.

Graph 4

Graph 5

Both Tai Kung Pao and The China Mail were mostly neutral or factual when they were writing about the refugees, though a modest number of articles did talk about them in a sympathetic tone. It is interesting to note that, while the refugees came from Mainland China, none of the articles in The China Mail – the foreign-owned newspaper – were found to have addressed the refugees in a hostile way, yet a limited amount of them did in Tai Kung Pao – the Chinese-owned newspaper.

Graph 6

Graph 7

Taken from Graph 8, it is clear that, when talking about the refugees, Tai Kung Pao predominately documented activities related to refugee management. For example, on October 23, 1938, the paper reported about the St. John Ambulance Brigade registering refugees who were sleeping rough on the streets and sending them to refugee camps. The traffic of refugees, the negative impacts of refugees (for example, probable robberies committed by refugees, as it was covered on December 8, 1938, and the increase in alcohol and cigarette imports that came with the growing number of population, as it was reported on November 3, 1938), the way refugees lived and the circumstances they faced were also covered occasionally, whereas conflicts in regard to the refugees and the positive impacts they had were not touched on at all. As

for the coverage in The China Mail (Graph 9), refugee management (e.g. how organisations provided support for refugees) and the traffic of refugees (e.g. the number of refugees entering Hong Kong) were the two most prominent topics, while the frames of morality, conflict and positive impact could not be identified from the articles. The rest of the frames were employed for around the same number of times in the sample.

Graph 8

Graph 9

Discussion

From the articles examined, it can be argued that the two newspapers did use multiple and different frames to report the refugee wave. Overall, the newspapers mainly used news articles to talk about the refugees in a neutral or factual way. It was foreseeable that news pieces would be the type of article that was used the most, as the research’s subject matter was, after all, newspapers. On the other hand, the fact that they mostly used the neutral or factual tone to cover stories suggests that they upheld the journalistic value of objectivity well. In terms of the typology and the tone of articles, the differences between Tai Kung Pao and The China Mail were slim. However, when it came to how they chose to frame the topic, there was a noticeable difference. Though the frames of refugee management and the traffic of refugees were both the most dominate frames in both newspapers, the refugee management frame in Tai

Kung Pao was used significantly more (63.2%) than the traffic of refugees frame (15.8%), whereas in The China Mail, perhaps due to the small sample size, there was not an apparently difference between how much the traffic of refugees frame (36.6%, or 15 pieces of articles) and the refugee management frame (24.4%, or 10 pieces of articles) were used. In fact, except for the refugee management frame, the traffic of refugees frame and the frames that were not used, none of the frames were used considerably more than the others in The China Mail, which implies that the paper covered the refugee wave in a comprehensive manner, referring to different topics to give the readers a broader understanding of the situation.

It could be observed during the research that a lot of articles which employed the refugee management frame in the two newspapers were about groups, organisations or the government holding meetings on how to relieve the refugees or exercising relief measures, which indicates that, even though the newspapers’ tone when talking about the refugees was mostly neutral, they were still sympathetic towards the refugees and was in support of them seeking safety in Hong Kong. The traffic of refugees frame employed by the newspapers mainly referred to the scene of refugees crossing the border between Mainland and Hong Kong. The reason for its regular usage could be that describing the scene of refugees running away from danger would be the most direct way of reporting the crisis, and that the entry of refugees was considered to be important information for the city’s people.

It is worth noting that the frames of conflict and positive impact were not detected from either of the newspapers, while the morality frame was only used once by Tai Kung Pao. The lack of usage of the conflict frame could be because that it was a common attitude among the people of Hong Kong at that time that they should help and support the refugees, thus there was no disagreement between whether relief measures should be taken or not. As the editorial published in The China Mail on November 29, 1938 wrote, “humane feeling will prevail over all other considerations”. However, the large number of refugees rushing into Hong Kong did

bring about a number of economic and social problems to the city, which is possibly a reason that the positive impact frame could not be found within the articles, as the writers could not envisage any positive influence the refugees could bring to Hong Kong. In addition, Semetko and Valkenburg explained that the morality frame is something that puts an issue “in the context of religious tenets or moral prescriptions” (2000, p96). As it has already been looked at, the two newspapers were careful with maintaining journalistic objectivity, which could be why they took care of leaving religious tenets out of the articles – the frame was only used once in an editorial.

As it was explained in the literature review, Entman (1993) and Scheufele (2000) had different ideas in regard to the practical function of framing. Entman (1993) believed that framing an item is to make selected aspects of an event more salient in order to highlight certain ways to evaluate the item, whereas Scheufele (2000) argued that framing invokes interpretive schemas on the audience to influence how they interpret information. From the articles inspected in the sample, it could be suggested that both views are, in a way, reasonable. For example, on November 26, 1938, in order to encourage citizens to donate food and clothing to the refugees, it was highlighted in The Chine Mail that “thousands… spent bitterly cold hours in open fields, cowering in ditches to shield themselves from the wind”, which supports Entman’s idea. In another article published in Tai Kung Pao on November 2, 1938, it3 was written that all refugees that were bailed out from the refugee camps by their families and friends were prohibited from leaving the New Territories. The regulation could be considered to be the government restricting the refugees’ freedom of movement. However, in the article, its purpose was said to be “to maintain Hong Kong’s security and sanitation”, and that too many refugees in the city would lead to the citizens of Hong Kong being agitated by the prospect of not having enough space to live in. In this case, limiting the refugees’ right to travel was framed as a way to protect Hong Kong’s native

3 The original text reads “關於保領難民辦法、仍按照前定規例執行、凡具有正式保證者、即可保🎧、但保🎧難民、雖於🎧營之後、亦只能住居新界元朗等地、任何一人、不能入居香港、此舉為當局維持港中治 安及衛生而設、在本港人口極度繁密之今日、苟令難民源源入港、則最低限度、香港居民亦受到樓宇恐慌 之影響也、”

citizens, which, according to Scheufele’s argument, had the possibility of influencing the readers’ opinion on the regulation.

Another matter that is worth discussing is the difference in the sample sizes between the two newspapers. Out of all the editions published within the two-month period, there were 114 articles in Tai Kung Pao that were related to the refugees, no matter if they were focused on them or only mentioned them. In The China Mail, there were only 41 articles. It would be tempting to argue that it could be because the Chinese community was more concerned about the refugees’ circumstances, whereas English- speaking foreigners in Hong Kong were less likely to be affected by the refugees due to their economic status and social position. However, it must be taken into account that many pieces in The China Mail were long, usually compiling all related information together in one article, whereas more pieces relevant to the refugees would usually be contained in each edition of Tai Kung Pao, with each of them being relatively shorter and only encompassing limited information.

Limitations

The most prominent limitation of this research is that the intercoder reliability test was not employed to test the coding system’s objectivity and validity. Due to the small size of the research, the coding was solely done by the researcher alone without the examination of external coders, thus there is a possibility of the codes being inconsistent and biased.

Furthermore, though as it has been stated in the methodology chapter that the two newspapers selected for this research were reasonable representations of Chinese- owned and foreign-owned newspapers in Hong Kong during the sample period, in no way can it be concluded that research done on other newspapers would generate the same results as this particular research. Other Chinese-owned newspapers or foreign- owned newspapers could have reported the refugee wave or addressed the refugees in a different manner. Hence, further research on more newspapers need to be conducted

before a more general conclusion on how refugees were portrayed by newspapers could be established.

Similarly, another limitation of this research is that the sample period is, though representative, too short to be conclusive. Studies done on other periods of time or a longer period of time during the refugee wave could generate different results. This research can serve as an indication of what the two newspapers generally covered about the refugees and how they did it, but there is no guarantee that the patterns remained the same throughout the entire period of the sample universe.

In addition, as content analysis is simply a descriptive research method, the results generated can only reveal what is in the sample, but cannot provide information on why they were produced (Neuendorf, 2002). As a result, by adopting the content analysis method, this research was capable of examining what tones and content were included in the articles, but it was not able to give reasons for why the authors used such tones or frames or in what ways could they potentially influence the readers.

Therefore, this research can only act as a foundation for further studies to build on.

Suggestions for future research

Due to its small scale, this research was only capable of studying two newspapers in a two-month period by using a basic form of the content analysis method. However, though preliminary, it can serve as a basis for future studies that focus on news coverage of the Chinese refugee wave to Hong Kong between 1937 and 1941, which is a topic of research that has not been given much attention to by academics. Ideally, future research should aim to diminish limitations that exist in this study and establish a better understanding of the issue. Research of larger scales should examine longer time frames and more newspapers to generate a more comprehensive conclusion of the questions.

In addition to newspapers, if it is possible to collect enough old radio recordings to conduct a study, research can also be done on how news programmes on radio talked about the refugees, as radio was just starting to gain popularity during the 1930s and the 1940s in Hong Kong (Clayton, 2004). A broader study on how different kinds of media talked about the refugee issue and if there were differences between their coverage would be able to produce new insights on the media industry in Hong Kong.

In regard to the question of which newspaper covered more about the refugees, an alternative research in which the unit of analysis is each word in the sample would be a good option to examine the issue. However, the differences between the English language and the Chinese language must be taken into consideration when conducting the research, as they are completely different in terms of syntax and lexicons, and a way to scientifically measure and compare their word counts should be developed first.

Furthermore, as it has been recognised in the limitations, this research has not been able to discover why the writers employ the tones and frames they used in the articles or how the articles could influence the readers. Further research could be done to investigate such issues by using other research methods such as qualitative content analysis and discourse analysis. According to Macnamara (2005, p5), media texts are “polysemic”, meaning that they are open to interpretation and carry different meanings for different people. Therefore, as a research method which is often used to study meanings and contextual codes (Shoemaker and Reese, 1996), qualitative content analysis can potentially offer deeper insights into how the articles would be received by the readers during the refugee wave. Also paying close attention to the context the topic of research is in, discourse analysis looks at how structures and patterns of a language used in texts contribute to the presentation of facts and ideologies (Fairclough, 1995). Therefore, it can be expected that the method can be used to propose ideas about why certain frames were employed and develop a broader understanding of the papers’ stances on the refugees.

Conclusion

In this study, a quantitative content analysis was done on how two newspapers in Hong Kong, namely Tai Kung Pao and The China Mail, covered the Chinese refugee wave to Hong Kong from October 13, 1938 to December 13, 1938. It can be concluded from the findings that, judging from the tone and content the articles examined carried, the papers were generally compassionate to the refugees. The two newspapers were similar in terms of their tone and type of articles used when reporting stories related to the refugees, however, the content in the articles in The China Mail were more comprehensive than that in Tai Kung Pao. Even though, unfortunately, this research was only able to identify the existence of such patterns and not why such patterns existed, it provides information that no previous studies have looked at before and leaves room for further and more thorough research on the topic.

Nowadays, 80 years later, if incoming refugees and asylum-seekers should be allowed to stay in Hong Kong and how people should treat them remain disputed issues in the city, and the local press continues to use different frames to write stories about them – for example, HK01, an online-based news organisation, earlier this year, published a series of features focusing on individuals who had been seeking asylum in Hong Kong for more than a decade4. By showing the readers the hardship they endured, HK01 campaigned for granting humanitarian visas to asylum-seekers in the city. In an age in which millions of people in the world have been forced to leave their homes, research on how the news media, an influential platform that plays a part in shaping public opinions, talk about refugee crises and the community has never been more needed. Hopefully, more intensive research projects on the topic will be carried out, and more can be known about news coverage on refugees in the future.

4 The features can be found in the following links: https://bit.ly/2GRIxGz https://bit.ly/2ZHHel4 https://bit.ly/2PB1OyR

Reference List

Ardèvol-Abreu, A. (2015). Framing Theory in Communication Research. Origins, Development and Current Situation in Spain. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 70(1), 423-450.

Babbie, E. (2013). The Practice of Social Research, 13th ed. Boston: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, p300. Available from: http://jsp.ruixing.cc/jpkc_xingfa/JC_Data/JC_Edt/lnk/20161105194206236.pdf [Accessed 14 March 2019].

Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communication research. New York: Free Press.

Bolton, K. (2003). Chinese Englishes: A Sociolinguistic History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ceoi, T. S. (2016). Hong Kong Memory: Since 1977 (我们香港这些年). Beijing: CITIC Press Group.

Census and Statistics Department (C&SD). (2012). 2011 Population Census – Summary Results. Hong Kong: Census and Statistics Department. Available from: https://www.census2011.gov.hk/pdf/summary-results.pdf [Accessed 26 February 2019].

Chan, C. T. (2018). Baandong Shidoi dik Syucing: Kongzin Shikei dik Hoenggong jyu Manhok (板蕩時代的抒情:抗戰時期的香港與文學/Lyricism in a Time of

Trouble: Hong Kong and Literature during the War of Resistance). Hong Kong: Chung Hwa Book Company (Hong Kong).

Chen, Q. (1987). Xianggang Jiushi Jianwenlu (香港旧事见闻录/A Sketchbook of Hong Kong’s Past). Hong Kong: Zhongyuan Publishing, p217.

Clayton, D. (2004). The Consumption of Radio Broadcast Technologies in Hong Kong, c. 1930-1960. The Economic History Review, 57(4), 691-726.

Collins Dictionaries. (2011). Collins Chinese Dictionary, 3rd edition. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Coman, C. and Cmeciu, C. (2014). Framing Chevron Protests in National and International Press. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 149(2014), 228-232.

D’Angelo, P. and Kuypers, J. A. (eds.) (2010). Doing News Framing Analysis: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives. New York: Routledge, p1.

de Vreese, C. H. (2005). News Framing: Theory and Typology. Information Design Journal & Document Design, 13(1), 51-62.

Deng, J. Z. (2018). Kangzhan Shiqi Xianggang Jiuwang Zhennan Tuanti (1935-1941) Jieshao (抗战时期香港救亡赈难团体1935-1941介绍/An Introduction of the Relief Organisations in Hong Kong during the Resistance War 1935-1941). Resistance War

Culture Analysis, 2018(00), 31-52.

Deng, K. S. and Lu, X. M. (1996). Yuegang’ao Jandia Guanxishi (粤港澳近代关系

史/The Modern History of the Relationship Between Canton, Hong Kong and Macau). Guangzhou: Guangdong People’s Publishing House, p273.

d’Haenens, L. and de Lange, M. (2001). Framing of Asylum Seekers in Dutch Regional Newspapers. Media Culture & Society, 23(6), 847-860.

Ding, J. (2014). Overseas Chinese Daily News and the Development of Chinese Society in Hong Kong, 1925-1995 (《華僑日報》與香港華人社會(1925-1995)) . Hong Kong: Joint Publishing (H.K.).

Endacott, G. B. (1978). Hong Kong Eclipse. New York: Oxford University Press, p12.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.

Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51-58.

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical Discourse Analysis. London: Longman.

Fan, S. C. (1974). The Population of Hong Kong. Paris: CICRED, 1-2.

Fung, C. M. (2005). Reluctant Heroes: Rickshaw Pullers in Hong Kong and Canton, 1874-1954. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Garrison, B. (1999). Professional Feature Writing, 3rd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., p89.

Gitlin, T. (1980). The Whole World is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmasking of the New Left. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, p21.

Hesse-Biber, S. N and Leavy, P. (2011). The Practice of Social Research, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, Inc, p228.

Holsti, O. R. (1968). Content Analysis. In: Lindzey, G. and Aronson, E. (eds.) The Handbook of Social Psychology, 2nd ed. Oxford: Addison-Wesley.

Insch, G. S., Moore, J. E. and Murphy, L. D. (1997). Content Analysis in Leadership Research: Examples, Procedures, and Suggestions for Future Use. The Leadership Quarterly, 8(1), 1-25.

Joeng, G. H. (2013). Hoenggong Zincin Boujip (香港戰前報業/The Newspaper Industry in Hong Kong before the War). Hong Kong: Joint Publishing (H.K.).

Keeble, R. (2001). Ethics for Journalists (Media Skills). London: Routledge, p95.

Kobayashi, H. and Shibata, Y. (2016). Nihon Gunseika No HongKong (ニホン グン

セイカ テキ ホンコン/Hong Kong under the Japanese Military Rule), edition in Chinese. Translated by Tian, Q., Li, X. and Wei, Y. F. Hong Kong: The Commercial Press (Hong Kong).

Lasswell, H. D. (1948). Power and Personality. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Lau, C. P. and Zhou, J. J (2009). Daily Life of Hong Kong during the Japanese Occupation (吞聲忍語:日治時期香港人的集體回憶). Hong Kong: Chung Hwa Book Company.

Law, K. Y. and Lee, K. M. (2006). Citizenship, Economy and Social Exclusion of Mainland Chinese Immigrants in Hong Kong. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 36(2), 217-242. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233015030_Citizenship_Economy_and_Soc ial_Exclusion_of_Mainland_Chinese_Immigrants_in_Hong_Kong [Accessed 26

February 2019].

Lee, G. S. (2000). A Comment on the Press of Hong Kong (香港報業百年滄桑). Hong Kong: Ming Pao Publications.

Lutz, C. A. and Collins, J. L. (1993). Reading National Geographic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p89.

Macnamara, J. (2005). Media Content Analysis: Its Uses, Benefits and Best Practice Methodology. Asia Pacific Public Relations Journal, 6(1), 1-34. Available from: https://amecorg.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Media-Content-Analysis-Paper.pdf [Accessed 15 March 2019].

Mizuoka, F. (2017). British Colonialism and “Illegal” Immigration from Mainland China to Hong Kong. In: Onjo, A. (ed.) Power Relations, Situated Practices, and the Politics of the Commons: Japanese Contributions to the History of Geographical Thought. Fukuoka: Kyushu University.

Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). The Content Analysis Guidebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Ngo, H. and Li, H. (2016). Cultural Identity and Adaptation of Mainland Chinese Immigrants in Hong Kong. American Behavioral Scientist, 60(5-6), 730-749.

Phillips, R. T. (1980). The Japanese Occupation of Hainan. Modern Asian Studies, 14(1), 93-109.

Qi, C. F., Zheng, Z. and Yan, H. J. (2015). Kangri Zhanzheng yu Zhongguo Shehui Bianqian (抗日战争与中国社会变迁/Anti-Japanese War and China’s Social Change). Beijing: Tuanjie Press, p19.

Qin, H. F. (2003). The State of the Refugees in Hong Kong Prior to its Occupation by the Japanese and the British-ruled Hong Kong’s Administration’s Policy (香港沦陷前难民境况和港英政策). Journal of Wuyi University, 5(2), 33-36.

Rose, S., Spinks, N. and Canhoto, I. (2014). Management Research: Applying the Principles. London: Routledge.

Sa, K. L. (1946). Xianggang Lunxian Riji (香港沦陷日记/Diary of the Fall of Hong Kong). Beijing: Joint Publishing.

Scheufele, D. A. (2000). Agenda-Setting, Priming, and Framing Revisited: Another Look at Cognitive Effects of Political Communication. Mass Communication and Society, 3(2-3), 297-316.

Scheufele, D. A. and Tewksbury, D. (2007). News Framing Theory and Research. In: Bryant, J. and Oliver, M. B. (eds.) Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. New York: Routledge, 17-33.

Semetko, H. A. and Valkenburg, P. M. (2000). Framing European Politics: A Content Analysis of Press and Television News. Journal of Communication, 50(2), 93-109.

Shoemaker, P. J. and Reese, S. D. (1996). Mediating the Message: Theories of Influences on Mass Media Content. White Plains: Longman.

Sinn, E. (1994). Growing with Hong Kong: The History of the Bank of East Asia (與

香港並肩邁進:東亞銀行 1919–1994). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, p27.

Sinn, E. (1997). Sewui Zouzik jyu Sewui Zyunbin (社會組織與社會轉變/Social Organisations and Social Transformation). In: Wang, G. W. (ed.) Hong Kong History: New Perspectives. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing (H.K.).

Snow, P. (2003). The Fall of Hong Kong: Britain, China and the Japanese Occupation. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ta Kung Pao. (1938). X gwan Camfaan Waanaam (X軍侵犯華南/The X Army Attacked South China). Ta Kung Pao, 13 October. Available from: https://bit.ly/2TeKp3v [Accessed 21 February 2019].

Terkildsen, N. and Schnell, F. (1997). How Media Frames Move Public Opinion: An Analysis of the Women’s Movement. Political Research Quarterly, 50(4), 879-900.

Ting, S. P. (1997). Liksi dik Zyunzip: Zikman Taihai dik Ginlap wo Jinzeon (歷史的轉折:殖民體系的建立和演進/The Transformation of History: The Establishment

and Evolution of the Colonial System). In: Wang, G. W. (ed.) Hong Kong History: New Perspectives. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing (H.K.).

Tsai, J. F. (2001). The Hong Kong People’s History of Hong Kong 1841-1945 (香港人之香港史 1841-1945). Hong Kong: Oxford University Press (China).

Tuchman, G. (1978). Making News: A Study in the Construction of Reality. New York: Free Press, p193.

Yan, L. (2008). Lun Zhanshi Qiangang Nanmin dui Xianggang Jingji de Tuidong (论

战时迁港难民对香港经济的推动/A Discussion of the Role of Wartime Refugees in Boosting Hong Kong’s Economy). Inheritance, October, 2008, 94-95.

Yu, J. L. (2009). Kangzhan Shiqi Guangdong Nanmin Ru Gang Jingkuang ji Gangying Zhengfu de Yingdui (抗战时期广东难民入港境况及港英政府的应对

/The Situation of Refugees from Guangdong Entering Hong Kong during the

Resistance War and Measures Undertook by the British Hong Kong Government).

Inheritance, January 2009, 106-107.

Valkenburg, P. M., Semetko, H. A. and de Vreese, C. H. (1999). The Effects of News Frames on Readers’ Thoughts and Recall. Communication Research, 26(5), 550-569.

Vrzic, I. (2013). Hong Kong Government’s Policies toward War Refugees, 1937-1941 (香港政府處理抵港難民的對策 (1937-1941)). Master’s thesis, National Chi Nan University.

Webb, E. J., Campbell, D. T., Schwartz, R. D. and Sechrest, L. (1968). Unobtrusive Measures: Nonreactive Research in the Social Sciences. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Wimmer, R. D. and Dominick, J. R. (2011). Mass Media Research: An Introduction, 9th ed. Boston: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. Available from: https://saleemabbas2008.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/1353087914- wimmer_dominick_mass_media_research_2011.pdf [Accessed 16 March 2019].

Wong, S. H. W., Ma, N. and Lam, W. M. (2016). Migrants and Democratization: The Political Economy of Chinese Immigrants in Hong Kong. Contemporary Chinese Political Economy and Strategic Relations: An International Journal, 2(2), 909-940.

Zhang, L. (1994). Kangrizhanzheng Shiqi Xianggang de Neidi Nanmin Wenti (抗日

战争时期香港的内地难民问题/The Mainland Refugee Problem in Hong Kong During the War of Resistance Against Japan). War of Resistance Against Japan Research, 4(1), 132-141.

Zhang, L. (2005). 20 Shiji Shangbanqi Xianggang Renkou Yanjiu (1901-1941 Nian) (20世纪上半期香港人口研究 (1901-1941年)). In: Institute of Modern History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, ed. 5th Academic Forum for the Youth at the

Institute of Modern History, CASS. Beijing, China. June 2003. Beijing: Social

Sciences Academic Press (China), 448-474.

Zhao, Y. Z. and Sun, P. (2018). A History of Journalism and Communication in China. London: Routledge.

Appendix 1

Coding Manual

Unit of Analysis: Each article

Name of newspaper:

1 = Tai Kung Pao

2 = The China Mail

Date of publication (Enter actual date as yymmdd, e.g. October 23, 1938 = 381023):

Number of article (Enter as date of publication dash number of article on the day, e.g. 381023-1):

Tone of article (Specifically towards the refugees):

1 = Hostile (Clearly negative) 2 = Neutral/Factual

3 = Sympathetic (Clearly supportive)

Content of article:

1 = Human interest

- Does the story provide a human example or “human face” on the issue?

- Does the story employ adjectives or personal vignettes that generate feelings of outrage, empathy-caring, sympathy, or compassion?

- Does the story emphasize how individuals and groups are affected by the issue/problem?

- Does the story go into the private or personal lives of the refugees?

- Does the story contain visual information that might generate feelings of outrage, empathy-caring, sympathy, or compassion?

2 = Responsibility

- Does the story suggest that some level of government has the ability to alleviate the problem?

- Does the story suggest that some level of the government is responsible for the issue/problem?

- Does the story suggest solution(s) to the problem/issue?

- Does the story suggest that an individual (or group of people in society) is responsible for the issue/problem?

- Does the story suggest the problem requires urgent action?

3 = Conflict

- Does the story reflect disagreement between parties-individuals-groups- countries?

- Does one party-individual-group-country reproach another?

- Does the story refer to two sides or to more than two sides of the problem or issue?

- Does the story refer to winners and losers?

4 = Negative impact

- Is there a mention of costs, degree of expense or financial losses now or in the future?

- Is there a reference to negative consequences of relieving the refugees?

- Is there a mention of refugees damaging or having the potential to damage the society, such as by committing crimes, polluting the environment or causing illness?

5 = Positive impact

- Is there a mention of financial gains now or in the future?

- Is there a reference to positive outcomes of relieving the refugees?

- Is there a mention of refugees contributing to or having the potential to contribute to the society, such as by increasing labour productivity, boosting intercultural communications or decreasing the price of food?

6 = Refugee management

- Is there a mention of how persons, groups, organisations or the government provide support and/or relief services to the refugees?

- Is there a mention of protection, overall management and/or coordination of the refugees?

- Is there a mention of the overall management of the refugee camps?

7 = Refugee life and circumstance

- Is there a mention of the circumstances refugees encounter?

- Is there a mention of how refugees live their lives?

- Is there a mention of the environment refugees settle in?

8 = Traffic of refugees

- Does the story describe the scene of refugees entering or leaving Hong Kong?

- Is there a mention of the number of refugees crossing the border, either entering or leaving Hong Kong?

- Is there a mention of refugees crossing the border, either entering or leaving Hong Kong?

- Is there a mention of the government restricting refugees from entering or leaving Hong Kong?

9 = Morality

- Does the story contain any moral message?

- Does the story make reference to morality, God, and other religious tenets?

- Does the story offer specific social prescriptions about how to behave?

Type of article:

1 = News

2 = Feature (e.g. human interest stories or reportage) 3 = Opinion (e.g. editorial, commentary, or column) 4 = Other